Summary:

Once a year, a tent city springs up overnight around the exhibition halls in Des Moines as farmers and their families pour in from across Iowa to attend the State Fair. After months of hard and often lonely work, farm families are given the chance to step out of their rural routines — picnic and gossip, sing and dance, take a chance at the hoopla stands, and strut their stuff in stiff competition for ribbons and prizes.

When the close-knit Frake family set out from Brunswick, Iowa, Abel's hog, Blue Boy rode proudly in the back of the truck — manicured, curried and rubbed to enameled perfection — ready to compete and win the sweepstakes, the highest honor which any hog could attain. Melissa, Abel's wife, had her hopes set on beating the competition with the prize-winning quality of her pickles. Their teenage children, Wayne and Margy, found themselves faced with a pickle of another kind. Although committed to sweethearts in their hometown, brother and sister are each seized by a new love that sweeps them along, secretly and illicitly, somewhere between the sweet taste of cotton candy and the breathtaking plunge of a roller coaster ride.

When the close-knit Frake family set out from Brunswick, Iowa, Abel's hog, Blue Boy rode proudly in the back of the truck — manicured, curried and rubbed to enameled perfection — ready to compete and win the sweepstakes, the highest honor which any hog could attain. Melissa, Abel's wife, had her hopes set on beating the competition with the prize-winning quality of her pickles. Their teenage children, Wayne and Margy, found themselves faced with a pickle of another kind. Although committed to sweethearts in their hometown, brother and sister are each seized by a new love that sweeps them along, secretly and illicitly, somewhere between the sweet taste of cotton candy and the breathtaking plunge of a roller coaster ride.State fairs were a subject that Phil Stong knew well. For several years his grandfather had been superintendent of the swine division at the Iowa State Fair and, as a reporter for the Des Moines Register, Stong was assigned to cover the evening stock shows at the fair. Iowa held its first state fair in 1854, and for some time fairs were held at various locations around the state before permanently settling in Des Moines. State Fair is very much an Iowa book, filled with incidents and details from the author's own life.

Although State Fair suggests a deep satisfaction and fondness for rural life, it shocked some readers in 1932 and was banned in the city library of Keosauqua, Iowa (Stong's hometown) for twenty-five years after it was published. However, judging from the success of the book and the enthusiasm shown for the movies that followed, most readers were captivated by the Frakes' down-home talk and whimsical humor and commended the author's portrayal of rural America.

Chapter 1

Saturday Evening

Abel Frake solemnly appraised the cigar which the Storekeeper laid before him. It was a thing of beautiful curves and a rich brown coat; its wrapper was limp and silky, and though, for all his air of connoisseurship, Abel knew no more about a cigar than any other smoker in Brunswick, he felt instinctively that this was good. For, finally, it was not a nickel cigar, but a three-for-a-quarter cigar — practically a ten-cent cigar.

With a consenting gesture he signaled for two more. "It's not reasonable a man should burn up the price of eight eggs — ten good days' work for a fair hen — in a Saturday evening and Sunday," he said, "but a man shouldn't stint himself all the time — it's only once a week."

The Storekeeper, only a little more than middle-aged despite the grey at his temples and the bald spot running up his high forehead, noted the purchase on a paper bag, at the end of a long line of figures. "You'd buy three nickel cigars anyway, Abel; you're just out ten cents. Next week you just work each one of your hens a little harder and you'll have that dime made up in no time."

Abel laughed. "You ever try to push extra work out of a hen? A hen ain't the kind you can push. Anyway, I guess it wouldn't do me much good to drive 'em. Mamma gets all the money from the hens for Fair Week and Christmas presents."

The Storekeeper smiled at Melissa Frake ironically. "You ever see any of that money, Mrs. Frake?"

Melissa's plump, agreeable face assumed a mock severity. "You can bet I do! I'm not saying it isn't a fight sometimes to keep it away from a man like Abel Frake, but I'm a match for him!"

The circle of loafers against the counters laughed softly with an effect almost choral. Years of laughing together at the proper moments had taught each of them to submerge his laughter in the group's. It was the unconscious response of men of uncertain social instincts.

"You sure you've got everything?" the Storekeeper asked.

Mrs. Frake slipped into a mild trance, checking off items in the air with her finger. While this thaumaturgy progressed, the loafers were respectfully silent. "Everything," she said, at last.

The Storekeeper, fully conscious of what was to ensue, began to arrange the heap of packages so that they could be easily divided. Mrs. Frake took a few steps this way, a few steps that way, and stared about at the great roomful of goods. Thirty feet of shelves, stretching from floor to ceiling, carried dry goods. There were cases containing harmonicas, air rifles, hairpins, patent medicines, and school books. At the back of the store was the tiny office with its safe, which said, "Please don't blow up this safe, it is just in case of fire. If you turn the knob it will open. Probably it will open if you just kick it."

Before the office was a rack of overalls, coats, and ready-made clothing. The Storekeeper stood behind a counter on the side of the store devoted to groceries and shoes. The hardware stock was in an adjoining room, unlighted. The main room was filled with the greenish-white glare of a gasoline-pressure lighting system.

"I think I might take a little sackful of candy," said Mrs. Frake. "Maybe a package of chewing gum for after dinner tomorrow."

The Storekeeper took two doubtful steps, as if the proposition were much too dubitable to justify his actually going to the candy counter.

"There it is," said Abel Frake, with unconvincing bitterness, "just because you work me into a little bit of extravagance she thinks she has to throw away the whole family fortune."

"I'm just as much entitled to my candy as you are to your cigars, Abel Frake," said Melissa with an attempt at fierceness, pouting lips which were still red and firm. "I guess I will have some candy," she added defiantly, to the Storekeeper, for the five-hundred-and-twentieth time in ten years of fifty-two Saturdays each. "Maybe she could make those hens work harder, Abel," said one of the loafers. "You say they're her hens." But this was said for only the onehundred-

and-fourth time, for it had been invented only two years before. Again the sympathetic moan of laughter filled the bright, shadowy room.

Abel uttered a low groan. "What kind of candy will it be, Mrs. Frake?" asked the Storekeeper triumphantly, as though he had just accomplished a miracle of salesmanship.

Her eyes glowed over the assortment of cheap nougats, gum-drops, hard sugar candies with colored flowers on their ends, pasty candy bananas, chocolate creams of an early vintage. The Storekeeper waited as though a decision were being made — as though she would not finally take ten cents' worth of chocolate caramels "with just a few lemon drops and a few pink peppermints — Margy likes them".

"I think," she said finally, "I'll take ten cents' worth of hard chocolates with just a few lemon drops and a few pink peppermints — Margy likes them." The Storekeeper weighed out twelve cents' worth of candy.

"And a package of Bloodmint Gum." Hastily. It was the five-hundred-and- twentieth afterthought of the ten years.

"How's Blue Boy looking, Abel?" The Storekeeper looked up over his scales, which showed that he was about to make one-fourth of a cent on a fifteen-cent transaction.

"Going to take him out of stud pretty soon. If he doesn't take sweepstakes at the Fair this year it's just about going to break up the whole Frake family — including Eph." Eph was the Hired Man. "Looks better than he looked last year — when he should've had it. They're going to have to raise some powerful hogs if they keep him out of the grand award this year."

The store door protested and opened, and two women entered. There was a babel of "Why, Melissa!" — "Why, Martha!" — "Alice, did you get that hat over in Pittsville?" and the three ladies withdrew to the show window — which was full of sacks of chickenfeed — disposed themselves comfortably on the sacks and began to talk in low but animated voices.

The loafers, with the Storekeeper and Abel Frake, on the other hand moved to the darker portion of the store near the ready-made suits. It was the Brunswick equivalent of the ladies' retirement to the drawing-room. A mild but hearty spirit of celebration filled the place. It was Saturday — eight-thirty, the very height of the evening.

The Storekeeper dropped his professional manner — very superficial at best — without any perceptible effort. The experiences of twenty years of country storekeeping had lined the Storekeeper's face with amiable, ironic lines. He believed, with Jack London's Sea Wolf, that Heaven ordains all things for the worst — but more mischievously than tragically. He thought of God as a slightly perverse, omnipotent small child, breaking His jam jars all over the Storekeeper's life. He gathered up the pieces and shook his finger at God.

"There's just one thing you want to watch out for, Abel," he said seriously. "Don't let your hog get too good."

Abel grinned as he awaited the resolution of this statement, for all Brunswick knew that the Storekeeper was slightly and amusingly mad. They respected his madness, for when the World War started he had crammed his store with stock, explaining that it was beyond belief that our Senators and Representatives in Congress should show the slight intelligence necessary to keep us out of it, and that prices would be higher. As a result he was now almost as well-to-do as Abel Frake.

"Because if he's the best hog, Abel, he'll never win the sweepstakes. If a hog, or a man, ever got what he was entitled to once, the eternal stars would quit making melody in their spheres, and all that. You have him about third or fourth best, Abel, and you'll do better, mark my words."

The loafers looked at each other and grinned. Abel smiled his thoughtful, almost wistful, smile and slapped the Storekeeper gently on the shoulder. "I'm going to have that hog in the finest shape I can possibly get him into, and never fear but what if he's the best he'll get the prize. Those men from Ames know their hogs."

"All right," said the Storekeeper, with humorous gloom, "but did you ever hear about automobile wrecks? Did you ever hear about lightning? Did you ever hear about earthquakes or hog cholera or acts of God? Suppose — as you're supposing, I don't suppose it — the judges should be good judges and suppose, even, they should be honest. What about hurricanes? Don't you get that hog too good."

Abel Frake laughed and took a cigar, which he had been fingering gently for some minutes, out of his coat pocket. "Guess I better smoke this," he said. "I've been looking forward to smoking these cigars, and now you've got me into the idea that probably they won't be much good. If they ain't you've got to take the other two back."

"Cigars," said the Storekeeper, "are something else. Providence has to keep its hands off cigars. If that cigar isn't a comfort and an inspiration, it'll only be because a tidal wave fell on it between Havana and here." The Storekeeper thought only in major catastrophes.

Abel split the tip of the cigar with an expert squeeze — the Storekeeper had shown him that trick — and lit it from the match which the Storekeeper held. He let the smoke curl up under his nose and smiled. He sighed with contentment.

"All right," he said, "you've taught me ways of prodigality and waste. You're the kind of a man that would lead a poor farmer to his ruin with your three-for-a-quarter cigars."

"Just as well be ruined one way as another," said the Storekeeper calmly. "If you didn't spend it on cigars you'd probably spend it on Bible tracts to annoy heathens, or for orphanages to soothe the consciences of people who don't want to be bothered looking out for orphans. You might even spend it on slop for that hog of yours. Aren't you going to permit yourself a little indulgence now and then? Are you going to spend your life seeing that that animated lard can astonishes civilization with the world's largest sausage-casings?"

Abel frowned at the Storekeeper. "Call me all the names you want to, but don't say anything against that hog. I've got faith in my hog. I believe in my hog."

"Yes," said the Storekeeper, "if there was anything lacking to beat your But-for-the-grace-of-God-shoat I suppose what you've just said would do it. I suppose he's so fat and mean-natured now that nothing could possibly keep him from being the best hog at the show. Well, that's Item One. Item Two, you're all set on him, so he's just as good as beat this very minute."

Abel Frake laughed deep in his throat, but quietly. "Blue Boy is the best Hampshire boar that ever breathed, right now. And, what's more, the judges will say so."

The Storekeeper looked at him thoughtfully. "They don't always work any way you could see Them. Your pig might win the prize, but your house would burn down or you'd catch rheumatism. You can't get away from Them."

Everyone within miles of Brunswick understood "Them" so well that there was no question. Abel Frake grinned at the Storekeeper.

"I'll make you a little bet. I'll bet you I go to the State Fair, and I'll bet you that Blue Boy wins sweepstakes, and I'll bet you my house doesn't burn down and that we all have a good time and are better off for it when the whole Fair is over."

"Abel," said the Storekeeper solemnly, "if you'd asked me I'd have given you ten to one. But you didn't ask me. I'm one to profit from a fellow-man's misfortunes; so I'll bet you. And I bet you that if I lose, something will've happened that we don't know about but that will be worse than anything you can think of. They're tricky."

Abel laughed. "But that way you can't lose. If we don't know of anything that happened, then you can just say that something happened we don't know about. How do I win?"

"If we don't learn about it by a couple of months after Fair time, I'll pay. I don't think They'll bother so much with you."

"It's a bet, then."

"It's a bet," said the Storekeeper, gravely and confidently, as though he had just bet on the rising of the sun. "I started me a little Fool Fund Wednesday. I got five dollars in it already and this will make ten."

"Fool Fund! What's that?"

"People think I'm a fool because I've got a notion of what things are all about. So I've begun to capitalize on that opinion. I took the Kellogg- Birge man from Keobuk for five dollars — the first five."

The loafers all laughed expectantly, for a story which they had already heard several times and liked, and Abel asked, "How did you do that?"

"Well, he came in here, and I said something about Hoover was going to be re-elected because there was no one in the country more markedly and pre-eminently unfitted for public office, and so he was a safe bet. This traveling-man said I was crazy about Hoover being re-elected and I was also crazy in general because there is a destiny that shapes our ends. So I made him a little bet and won five dollars."

"What was the bet?"

The Storekeeper looked mildly bored. "I said if you was driving nails in a board and reaching behind you for the nails, it would be arranged so that you would pick up more of the nails by the point, and have to turn them over, than you would pick up by the head end so that you could drive them without any trouble. Out of a hundred nails."

"Tell him how it come out," said one of the loafers who had heard a dozen times at least.

"It came out seventy-three to twenty-seven, so I took the money."

Abel laughed. "I'm glad you won five dollars so easy, because it will make me feel better about taking your money after the Fair. Your Fool Fund is going to wind up with no assets and no liabilities just two months after Fair Week."

The Storekeeper shook his head. "Except for the five dollars, which anyone in the general merchandising business can use, I sure hope so." There was a faint flurry at the front of the store. "Abel! Do you suppose we ought to be getting back? The Hired Man went over to Pittsville and there isn't a soul on the place."

"Took his wife and kids over to the moving pictures," Abel explained to the loafers — even such simple things were worthy of explanation. "I think it's worth while for him to get out occasionally."

He moved up to the front of the store and the Storekeeper followed him. The loafers settled down to another hour of conversation before the Storekeeper's closing time.

"Good night!"

"Good night, Mrs. Frake. You got your sack of candy?" "Never fear I'd forget that." She went out, laughing.

Saturday Evening

Abel Frake solemnly appraised the cigar which the Storekeeper laid before him. It was a thing of beautiful curves and a rich brown coat; its wrapper was limp and silky, and though, for all his air of connoisseurship, Abel knew no more about a cigar than any other smoker in Brunswick, he felt instinctively that this was good. For, finally, it was not a nickel cigar, but a three-for-a-quarter cigar — practically a ten-cent cigar.

With a consenting gesture he signaled for two more. "It's not reasonable a man should burn up the price of eight eggs — ten good days' work for a fair hen — in a Saturday evening and Sunday," he said, "but a man shouldn't stint himself all the time — it's only once a week."

The Storekeeper, only a little more than middle-aged despite the grey at his temples and the bald spot running up his high forehead, noted the purchase on a paper bag, at the end of a long line of figures. "You'd buy three nickel cigars anyway, Abel; you're just out ten cents. Next week you just work each one of your hens a little harder and you'll have that dime made up in no time."

Abel laughed. "You ever try to push extra work out of a hen? A hen ain't the kind you can push. Anyway, I guess it wouldn't do me much good to drive 'em. Mamma gets all the money from the hens for Fair Week and Christmas presents."

The Storekeeper smiled at Melissa Frake ironically. "You ever see any of that money, Mrs. Frake?"

Melissa's plump, agreeable face assumed a mock severity. "You can bet I do! I'm not saying it isn't a fight sometimes to keep it away from a man like Abel Frake, but I'm a match for him!"

The circle of loafers against the counters laughed softly with an effect almost choral. Years of laughing together at the proper moments had taught each of them to submerge his laughter in the group's. It was the unconscious response of men of uncertain social instincts.

"You sure you've got everything?" the Storekeeper asked.

Mrs. Frake slipped into a mild trance, checking off items in the air with her finger. While this thaumaturgy progressed, the loafers were respectfully silent. "Everything," she said, at last.

The Storekeeper, fully conscious of what was to ensue, began to arrange the heap of packages so that they could be easily divided. Mrs. Frake took a few steps this way, a few steps that way, and stared about at the great roomful of goods. Thirty feet of shelves, stretching from floor to ceiling, carried dry goods. There were cases containing harmonicas, air rifles, hairpins, patent medicines, and school books. At the back of the store was the tiny office with its safe, which said, "Please don't blow up this safe, it is just in case of fire. If you turn the knob it will open. Probably it will open if you just kick it."

Before the office was a rack of overalls, coats, and ready-made clothing. The Storekeeper stood behind a counter on the side of the store devoted to groceries and shoes. The hardware stock was in an adjoining room, unlighted. The main room was filled with the greenish-white glare of a gasoline-pressure lighting system.

"I think I might take a little sackful of candy," said Mrs. Frake. "Maybe a package of chewing gum for after dinner tomorrow."

The Storekeeper took two doubtful steps, as if the proposition were much too dubitable to justify his actually going to the candy counter.

"There it is," said Abel Frake, with unconvincing bitterness, "just because you work me into a little bit of extravagance she thinks she has to throw away the whole family fortune."

"I'm just as much entitled to my candy as you are to your cigars, Abel Frake," said Melissa with an attempt at fierceness, pouting lips which were still red and firm. "I guess I will have some candy," she added defiantly, to the Storekeeper, for the five-hundred-and-twentieth time in ten years of fifty-two Saturdays each. "Maybe she could make those hens work harder, Abel," said one of the loafers. "You say they're her hens." But this was said for only the onehundred-

and-fourth time, for it had been invented only two years before. Again the sympathetic moan of laughter filled the bright, shadowy room.

Abel uttered a low groan. "What kind of candy will it be, Mrs. Frake?" asked the Storekeeper triumphantly, as though he had just accomplished a miracle of salesmanship.

Her eyes glowed over the assortment of cheap nougats, gum-drops, hard sugar candies with colored flowers on their ends, pasty candy bananas, chocolate creams of an early vintage. The Storekeeper waited as though a decision were being made — as though she would not finally take ten cents' worth of chocolate caramels "with just a few lemon drops and a few pink peppermints — Margy likes them".

"I think," she said finally, "I'll take ten cents' worth of hard chocolates with just a few lemon drops and a few pink peppermints — Margy likes them." The Storekeeper weighed out twelve cents' worth of candy.

"And a package of Bloodmint Gum." Hastily. It was the five-hundred-and- twentieth afterthought of the ten years.

"How's Blue Boy looking, Abel?" The Storekeeper looked up over his scales, which showed that he was about to make one-fourth of a cent on a fifteen-cent transaction.

"Going to take him out of stud pretty soon. If he doesn't take sweepstakes at the Fair this year it's just about going to break up the whole Frake family — including Eph." Eph was the Hired Man. "Looks better than he looked last year — when he should've had it. They're going to have to raise some powerful hogs if they keep him out of the grand award this year."

The store door protested and opened, and two women entered. There was a babel of "Why, Melissa!" — "Why, Martha!" — "Alice, did you get that hat over in Pittsville?" and the three ladies withdrew to the show window — which was full of sacks of chickenfeed — disposed themselves comfortably on the sacks and began to talk in low but animated voices.

The loafers, with the Storekeeper and Abel Frake, on the other hand moved to the darker portion of the store near the ready-made suits. It was the Brunswick equivalent of the ladies' retirement to the drawing-room. A mild but hearty spirit of celebration filled the place. It was Saturday — eight-thirty, the very height of the evening.

The Storekeeper dropped his professional manner — very superficial at best — without any perceptible effort. The experiences of twenty years of country storekeeping had lined the Storekeeper's face with amiable, ironic lines. He believed, with Jack London's Sea Wolf, that Heaven ordains all things for the worst — but more mischievously than tragically. He thought of God as a slightly perverse, omnipotent small child, breaking His jam jars all over the Storekeeper's life. He gathered up the pieces and shook his finger at God.

"There's just one thing you want to watch out for, Abel," he said seriously. "Don't let your hog get too good."

Abel grinned as he awaited the resolution of this statement, for all Brunswick knew that the Storekeeper was slightly and amusingly mad. They respected his madness, for when the World War started he had crammed his store with stock, explaining that it was beyond belief that our Senators and Representatives in Congress should show the slight intelligence necessary to keep us out of it, and that prices would be higher. As a result he was now almost as well-to-do as Abel Frake.

"Because if he's the best hog, Abel, he'll never win the sweepstakes. If a hog, or a man, ever got what he was entitled to once, the eternal stars would quit making melody in their spheres, and all that. You have him about third or fourth best, Abel, and you'll do better, mark my words."

The loafers looked at each other and grinned. Abel smiled his thoughtful, almost wistful, smile and slapped the Storekeeper gently on the shoulder. "I'm going to have that hog in the finest shape I can possibly get him into, and never fear but what if he's the best he'll get the prize. Those men from Ames know their hogs."

"All right," said the Storekeeper, with humorous gloom, "but did you ever hear about automobile wrecks? Did you ever hear about lightning? Did you ever hear about earthquakes or hog cholera or acts of God? Suppose — as you're supposing, I don't suppose it — the judges should be good judges and suppose, even, they should be honest. What about hurricanes? Don't you get that hog too good."

Abel Frake laughed and took a cigar, which he had been fingering gently for some minutes, out of his coat pocket. "Guess I better smoke this," he said. "I've been looking forward to smoking these cigars, and now you've got me into the idea that probably they won't be much good. If they ain't you've got to take the other two back."

"Cigars," said the Storekeeper, "are something else. Providence has to keep its hands off cigars. If that cigar isn't a comfort and an inspiration, it'll only be because a tidal wave fell on it between Havana and here." The Storekeeper thought only in major catastrophes.

Abel split the tip of the cigar with an expert squeeze — the Storekeeper had shown him that trick — and lit it from the match which the Storekeeper held. He let the smoke curl up under his nose and smiled. He sighed with contentment.

"All right," he said, "you've taught me ways of prodigality and waste. You're the kind of a man that would lead a poor farmer to his ruin with your three-for-a-quarter cigars."

"Just as well be ruined one way as another," said the Storekeeper calmly. "If you didn't spend it on cigars you'd probably spend it on Bible tracts to annoy heathens, or for orphanages to soothe the consciences of people who don't want to be bothered looking out for orphans. You might even spend it on slop for that hog of yours. Aren't you going to permit yourself a little indulgence now and then? Are you going to spend your life seeing that that animated lard can astonishes civilization with the world's largest sausage-casings?"

Abel frowned at the Storekeeper. "Call me all the names you want to, but don't say anything against that hog. I've got faith in my hog. I believe in my hog."

"Yes," said the Storekeeper, "if there was anything lacking to beat your But-for-the-grace-of-God-shoat I suppose what you've just said would do it. I suppose he's so fat and mean-natured now that nothing could possibly keep him from being the best hog at the show. Well, that's Item One. Item Two, you're all set on him, so he's just as good as beat this very minute."

Abel Frake laughed deep in his throat, but quietly. "Blue Boy is the best Hampshire boar that ever breathed, right now. And, what's more, the judges will say so."

The Storekeeper looked at him thoughtfully. "They don't always work any way you could see Them. Your pig might win the prize, but your house would burn down or you'd catch rheumatism. You can't get away from Them."

Everyone within miles of Brunswick understood "Them" so well that there was no question. Abel Frake grinned at the Storekeeper.

"I'll make you a little bet. I'll bet you I go to the State Fair, and I'll bet you that Blue Boy wins sweepstakes, and I'll bet you my house doesn't burn down and that we all have a good time and are better off for it when the whole Fair is over."

"Abel," said the Storekeeper solemnly, "if you'd asked me I'd have given you ten to one. But you didn't ask me. I'm one to profit from a fellow-man's misfortunes; so I'll bet you. And I bet you that if I lose, something will've happened that we don't know about but that will be worse than anything you can think of. They're tricky."

Abel laughed. "But that way you can't lose. If we don't know of anything that happened, then you can just say that something happened we don't know about. How do I win?"

"If we don't learn about it by a couple of months after Fair time, I'll pay. I don't think They'll bother so much with you."

"It's a bet, then."

"It's a bet," said the Storekeeper, gravely and confidently, as though he had just bet on the rising of the sun. "I started me a little Fool Fund Wednesday. I got five dollars in it already and this will make ten."

"Fool Fund! What's that?"

"People think I'm a fool because I've got a notion of what things are all about. So I've begun to capitalize on that opinion. I took the Kellogg- Birge man from Keobuk for five dollars — the first five."

The loafers all laughed expectantly, for a story which they had already heard several times and liked, and Abel asked, "How did you do that?"

"Well, he came in here, and I said something about Hoover was going to be re-elected because there was no one in the country more markedly and pre-eminently unfitted for public office, and so he was a safe bet. This traveling-man said I was crazy about Hoover being re-elected and I was also crazy in general because there is a destiny that shapes our ends. So I made him a little bet and won five dollars."

"What was the bet?"

The Storekeeper looked mildly bored. "I said if you was driving nails in a board and reaching behind you for the nails, it would be arranged so that you would pick up more of the nails by the point, and have to turn them over, than you would pick up by the head end so that you could drive them without any trouble. Out of a hundred nails."

"Tell him how it come out," said one of the loafers who had heard a dozen times at least.

"It came out seventy-three to twenty-seven, so I took the money."

Abel laughed. "I'm glad you won five dollars so easy, because it will make me feel better about taking your money after the Fair. Your Fool Fund is going to wind up with no assets and no liabilities just two months after Fair Week."

The Storekeeper shook his head. "Except for the five dollars, which anyone in the general merchandising business can use, I sure hope so." There was a faint flurry at the front of the store. "Abel! Do you suppose we ought to be getting back? The Hired Man went over to Pittsville and there isn't a soul on the place."

"Took his wife and kids over to the moving pictures," Abel explained to the loafers — even such simple things were worthy of explanation. "I think it's worth while for him to get out occasionally."

He moved up to the front of the store and the Storekeeper followed him. The loafers settled down to another hour of conversation before the Storekeeper's closing time.

"Good night!"

"Good night, Mrs. Frake. You got your sack of candy?" "Never fear I'd forget that." She went out, laughing.

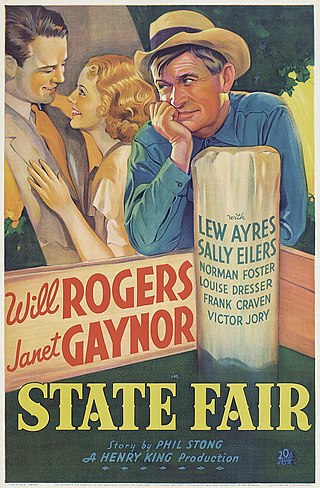

Release Date: February 10, 1933

Release Time: 97 minutes

Director: Henry King

Cast:

Janet Gaynor as Margy Frake

Will Rogers as Abel Frake

Lew Ayres as Pat Gilbert

Sally Eilers as Emily Joyce

Norman Foster as Wayne Frake

Louise Dresser as Melissa Frake

Frank Craven as Storekeeper

Victor Jory as Hoop Toss Barker

Frank Melton as Harry Ware

Erville Alderson as Martin(uncredited)

Hobart Cavanaugh as Professor Fred Coin(uncredited)

Harry Holman as Professor Tyler Cramp(uncredited)

Awards:

1933 Academy Awards

Paul Green, Sonya Levien - Best Writing (Adaptation) - Nominated

Outstanding Production - Nominated

Philip Duffield Stong (January 27, 1899 – April 26, 1957) was an American author, journalist and Hollywood scenarist. He is best known for writing the novel State Fair, on which three films (1933, 1945, and 1962) and the hit Rodgers and Hammerstein musical were based. Phil Stong's children's classic, Honk the Moose, illustrated by Kurt Wiese, was placed on Cattermole's 100 Best Children's Books of the 20th Century list and was 1936 Newbery Honor Book. Honk the Moose also won the Lewis Carroll Shelf Award in 1970.

Stong was born in Pittsburg, Iowa, a village no longer found on maps. Pittsburg was on the west side of the Des Moines River in southeast Iowa's Van Buren county. Young Phil was the son of Benjamin and Ada Evesta Duffield Stong. Father Ben ran a general store in Pittsburg and then later a variety store in Keosauqua, the county seat of Van Buren County, where he was also postmaster.

Phil Stong attended both elementary school and high school in Keosauqua and then went to Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa.

As a boy, Stong loved to read, especially works by Mark Twain, and decided to be a writer in his teens when he sold his first magazine story for $1. After graduation in 1919 he taught in the high school at Biwabik, Minnesota, a town on the Mesabi Iron Range north of Duluth. The young man found life in Biwabik fascinating because of the many different ethnic groups living in the area. Later, Stong set a novel, The Iron Mountain, and a children's book, Honk the Moose, in the Iron Range. Honk the Moose is recognized as a children’s classic and the people in the book were based on real folks and many of the buildings in the book are still standing. In the year 2000, Biwabik finally ordered and installed a big fiberglass moose in the town square, commemorating Honk.

Although Phil Stong enjoyed working as a teacher, he continued to strive to become a creative writer and eventually turned from teaching to the practice of journalism. When the opportunity arose, he went to work as a reporter and editorial writer for the Des Moines Register. In 1925, at age 26, Stong returned to New York, where he worked first as a wire editor for the Associated Press and then as a copy editor and feature writer for the North American Newspaper Alliance. In 1927 he went to Boston to interview Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti just before their execution, an experience he considered one of the most important in his life. Later, he was with the magazines Liberty and Editor and Publisher, and then Sunday feature editor of the newspaper the New York World, and finally an advertising writer for Young and Rubicam Advertising Agency.

On November 8, 1925, at the time he moved to New York, Phil Stong married Virginia Maude Swain, a reporter on the Register's sister newspaper, the Tribune.

Stong credited his wife with encouraging him in his writing. When reminiscing about the beginnings of his most famous novel, State Fair, Stong later said, "I was working in the publicity department of one of the few good advertising firms in the world when Mrs. Stong suggested that I do something about my native State's great harvest festival, the Fair.” This happened in the summer of 1931. On July 28, he wrote to family back in Iowa: "I've finally got a novel coming in fine shape. I've done 10,000 words on it in three days and I get more enthusiastic every day. . . . I hope I can hold up this time. I always write 10,000 swell words and then go to pieces.”

State fairs were a subject that Phil Stong knew well. For several years his grandfather had been superintendent of the swine division at the Iowa State Fair. Stong attended his first Iowa State Fair in 1908 and got lost trying to find his parents' tent on the campgrounds.

He never got lost at the fair again. Then, while a reporter with the Des Moines Register, Stong was assigned to cover the evening stock shows at the fair. American agricultural fairs were and still are a combination of education and festivity, and State Fair is very much an Iowa book, filled with incidents and details from the author's own life. While the setting of a state fair in the early part of the twentieth century is accurately portrayed, Stong was of course writing as a novelist and not as a historian. The author was creating an artistic representation of the fair, not presenting the literal truth, and his novel bubbles with whimsy and humor.

State Fair was Stong's thirteenth novel and first book to be published. After its success, Phil Stong went on to write more than forty books, many of them set in the Keosauqua area. When not writing adult fiction, he tried his hand at children's books. "I use the pieces to clear my throat between books to remind myself that direction, simplicity, and suspense are the sine qua non of all narrative writing." His favorite among his own books was Buckskin Breeches (1937), a historical novel based on his grandfather Duffield's memories of frontier Iowa.

With the income he earned from State Fair and selling the film rights, Stong was able to buy his pride and joy, the 400-acre Linwood Farm that had once belonged to his mother's family just north of the ghost town of Pittsburg on the west side of the Des Moines River.

In addition to his novels, his short stories were published in most of the leading national magazines of the time, and he wrote several screenplays. Stong's The Other Worlds: 25 Modern Stories of Mystery and Imagination, was considered by Robert Silverberg (in the foreword to Best of the Best: 20 Years of the Year's Best Science Fiction) to be the first anthology of science fiction. Compiling stories from 1930s pulp magazines, along with what Stong called "Scientifiction", The Other Worlds also contained works of horror and fantasy.

Phil Stong died at his home in Washington, Connecticut, in 1957, and was buried at Oak Lawn Cemetery in Keosauqua.

About his writing career, he once said, "Fell while trying to clamber out of a low bathtub at the age of two. Became a writer. No other possible career."

Film

No comments:

Post a Comment